Visiting Joshua Tree’s Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum

A black Mazda 3 pulls into one of the few open parking spots located at 63030 Blair Lane. Less than a minute later, a silver Nissan Sentra eases into the other free space. A group of millennials exit the second vehicle, cameras in hand, fedoras and snarky t-shirts adorning their bodies. They make their way inside something my grandfather would have likely labeled a “junkyard.”

It appears nearly everyone walking this junkyard is Caucasian, everyone except for the author of this article (me) and a Guatemalan-American associate traveling with me. We have a dog with us, but even he’s white. We’re initially not sure what to make of this place, but then we notice that perhaps neither is the posse walking ahead of us. It’s their pause at one semblance of “junk” near the entrance that beckons our attention. Positioned up against a makeshift brick wall are a water fountain and toilet. Signs above the objects provide quick clarity for the group’s pause: the one hanging over the fountain has the words “Whites” inscribed on it, and another above the toilet reads “Colored.”

This is The Noah Purifoy Desert Art Museum and there are some very direct and often more opaque references to racial inequality represented through his piles of junk.

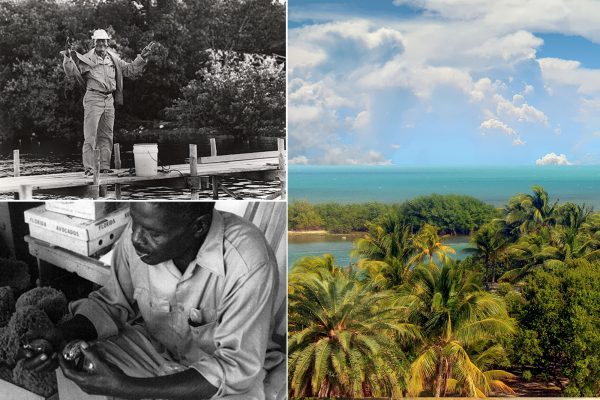

Noah was born in Alabama back in 1917, and that segregated upbringing is on full display in the piece of art staring back at us. After graduating from Alabama State University in 1943, Purifoy relocated to Los Angeles, California where he worked as a social worker. Feeling unfilled in his profession, in 1953 he began studying at what is known today as CalArt. That education would eventually lead him to becoming the co-founder of the Watts Tower Art Center. It was there in the shadows of the monuments Simon Rodia built that Purifoy likely developed his appreciation for using found objects to create social commentary.

After the 1965 Watts Rebellion leveled the predominantly Black community, Purifoy began amassing scraps from ruined buildings which he used to create pieces for the 66 Signs of Neon exhibit. Roughly 50 works of art made from debris and salvaged materials were he and a partner’s means of interpreting “the August event.” In the two decades that followed, Purifoy “dedicated himself to the found object art, and to using it as a tool for social change.”

And then came the desert.

It was during the final 14 years of his life, after relocating to Joshua Tree, California, that this sculptor’s most important work began. The harsh environment would become Noah Purifoy’s ultimate canvas: the junk seen scattered throughout the property today, not really junk at all, more like acrylic paints, and the scorching environment: his brush.

“I do not wish to be an artist, I only wish that art enables me to be.” – Noah Purifoy

One of the reasons Purifoy is said to have relocated to the high desert was because no museums in LA would show his work. His solution? Building a museum of his own. Unlike other artists of a different hue, Purifoy had no money during the later years of his life, no galleries bankrolling projects, or assistants helping him create. Surviving on a meager social security check, he couldn’t afford living in LA, so in his 70s, he relocated to Joshua Tree. It was here that he connected with locals to source debris and other materials.

Most of the work on his property was constructed without assistance. If you’ve been to the desert in the summer, it’s nearly impossible to imagine an elderly man building something this grand in such an unforgiving environment, but Purifoy labored until his eighties when could no longer move without the assistance of a wheelchair. He passed away a few years later in 2004, but his commentary on inequality lives on for posses of all colors to experience.

As for LACMA, they finally did exhibit his work, as did London’s Tate Modern, New York’s MOMA, DC’s National Gallery of Art and LA’s Getty Center and Broad Museum and LACMA.

The Noah Purifoy Desert Art Museum is located in Joshua Tree, California and is open seven days a week. It, like a lot of places you find in Joshua Tree, is proud to welcome people of all colors, religions and backgrounds, a very different world than the once segregated Alabama Noah grew up in.

Eric has revolved in and out of passport controls for over 20 years. From his first archaeological field school in Belize to rural villages in Ethiopia and Buddhist temples in Laos, Eric has come smile to smile with all walks of life. A writer, photographer and entrepreneur, the LA native believes the power of connectivity and community is enriched through travel.