This Ranger Thinks More Black Folks Need To Visit National Parks

When COVID-19’s stranglehold on the travel industry – and entire Black travel movement for that matter – subsides, I wager few African-Americans will venture to Asia. Thousands will return to collecting experiences across Europe or Latin America. But most of us will hit the road to explore America. Vegas, Miami, Los Angeles, Oakland, Brooklyn, and Atlanta will be popular options and are certainly worthy of tourism, but fewer will travel to national parks: one US ranger is hoping to change their minds.

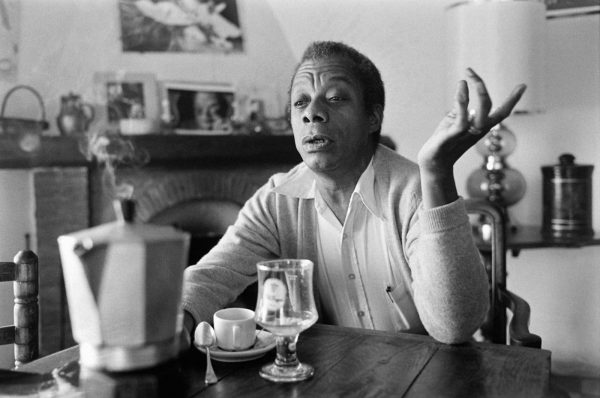

For over a decade, Shelton Johnson has been tasked with preserving and celebrating the historical connections between African-Americans and the National Parks. Shelton’s work takes place in Yosemite Valley where he operates as a ranger, educator, author, guide, historian and actor. On Sunday evenings, his theater presentations give his mostly Caucasian audience a firsthand glimpse into the lives of America’s first park rangers: Buffalo Soldiers.

African-Americans In The Park System

The all African-American calvary protected Yosemite from poachers and timber thieves during the summers of 1899, 1903 and 1904. They also helped install some of the park system’s early hiking trails, including one to the peak of Mount Whitney, the tallest mountain in the contiguous United States with an elevation of 14,505 feet. Shelton believes that African-Americans have a connection to the NPS not only because of our efforts in birthing “America’s Greatest Gift” (National Parks), but because of our pre-colonial history.

“I think what people of color, especially African-Americans, are missing is that these are environments where you can reconnect with something that is ancestral,” Johnson tells TravelCoterie’s Kevin Frazier. “This is innate to our blood, this is innate to our ancestry, this is innate to our own history not just as human beings, but as Africans in America, not necessarily African-Americans.”

Black People Don’t Visit Parks

Statistically however, our relationship with National Parks is lacking. African-Americans only make up 7-percent of annual park visitors, Latinos 9-percent and the Asian population, a mere 3-percent. Collectively, people of color make up 19 percent of national park visitors despite making up 40-percent of the US population. Shelton and TravelCoterie hopes to see those number improve post coronavirus.

“When we were indigenous native Africans from the West Coast of Africa brought here during the Atlantic slave trade … we were Africans arriving on these shores. We had an innate understanding of the natural world, we utilized the plants, we knew the animals that were all around, we had kinship with the world around us. The part of us that was that kind of African was slowly eroded away, wriggled away, until we became who we are now: a people that descend from indigenous Africans, who now avoid the experience of being out in the wild. And slavery has a lot to do with that experience,” the Detroit native explains.

“Our people going out into the mountains, going into the forest, is reclaiming that which is African. You can find that which was African in America because all you need is the natural world around you.”

The Conclusion

African-Americans and land have had an estranged relationship since emancipation. No one can fault our freed ancestors for fleeing rural landscapes in search of opportunity in America’s urban environments. Our generational disdain for soil, nature and the woods is more than justified. Terrifying things happened to our people in those woods. And so our connection to land in America is a tainted one, but our connection to land in general predates the diaspora. This realization isn’t universal throughout our communities, but an awakening is slowly happening amongst African-Americans looking to reconnect with the wild. So take it from the late Sharon Jones when planning your post COVID-19 getaway, “This land is your land.” It’s time for us to explore our land and reconnect.

Eric has revolved in and out of passport controls for over 20 years. From his first archaeological field school in Belize to rural villages in Ethiopia and Buddhist temples in Laos, Eric has come smile to smile with all walks of life. A writer, photographer and entrepreneur, the LA native believes the power of connectivity and community is enriched through travel.